When we look back at the images of Empire Windrush, we see that most of the passengers were young Black men. They were dressed impeccably, and they arrived full of hopes and dreams.

Their journey to ‘the motherland’ was for many an opportunity to build on their already happy and stable lives in the Caribbean. As my late Grandad said before he passed, ‘I did not have to come to England, I was doing well back home’. However, the constant adverts in Jamaica about supporting the motherland led to a journey to England that was driven by a patriotic love for Queen and Country as well as the dream to realise the lofty promises offered by Great Britain.

However, far from seeing the promised gold-paved streets, the smiles quickly turned to tears and heartbreak. The much-showcased abundance of opportunity turned to hostility and systematic exclusion. Before they knew it, prominent figures such as Enoch Powell and many others in British society wanted to send them home, to keep Britain White.

All this happened decades ago, but the trauma of that period lives on, economically, socially, and of course, mentally. Yet today it is often swept under the carpet, and today’s contemporary discussion about inequalities misses the trauma of this historical context. We do not ask: What was it about our British society that turned the smiles of many of those impeccably dressed, smiling, gentle, and friendly Black men into hardship, depression, and anxiety?

Importantly to what extent do those conditions still exist for Black men today?

The justification of a system rooted in fear

The Black man in Britain has consistently been faced with suspicion and fear. This is not only a fear of violence but also a fear of success. This is famously encapsulated in the words of Enoch Powell:

“In this country, in 15 or 20 years’ time, the Black man will have the whip hand over the White man”.

This fear of Black men’s success has been seen by too many as a threat to that of White people, particularly in the minds of the far-right. The whip-hand expression means to have a position of power, advantage and control over White people which was a primary fear of Enoch Powell and his supporters. How do you mitigate against the Black man having the whip hand? Well the answer is through oppression, exclusion and subjugation through systems and institutions.

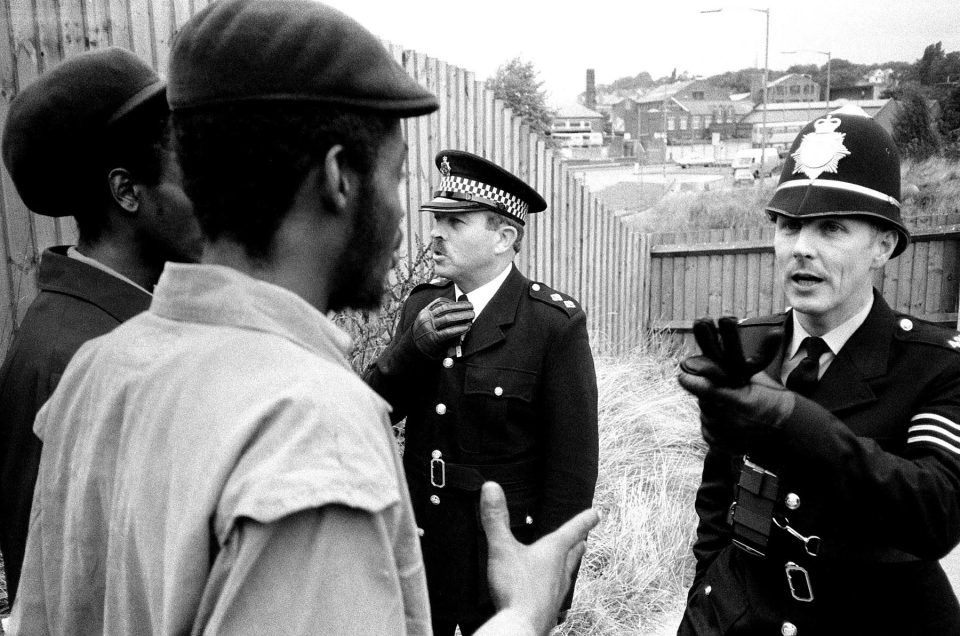

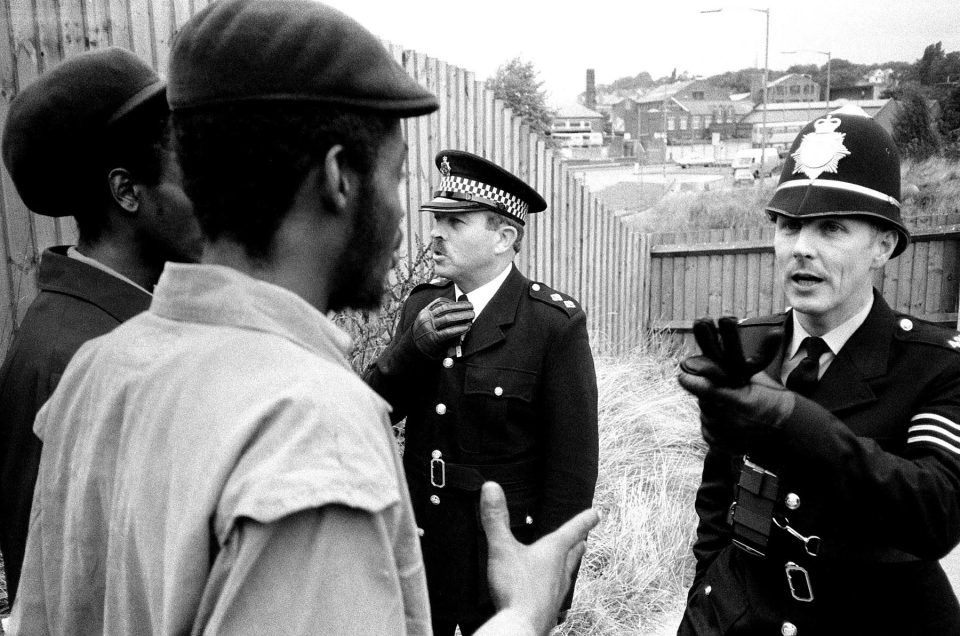

This lie of a zero-sum game society where if a particular group prospers then others will fail has taken a deep root in British society. Due to this pervasive lie and fear, this has led to systems and institutions that purposely systematically excluded Black men across multiple institutions. This can be seen in the colour bar, educationally subnormal schools, and discrimination in access to finance, housing and with mental health institutions.

The success of Black men was seen as something that undermines the presumed ‘social and racial order of society’. It undermines the false narrative that Black people are simply not capable enough and that there are no systemic failures but rather a lack of progress is something that is just embedded due to genetics or culture. Without these pervading narratives, then the system of inequality cannot be justified.

As stated by Dr Allison Wirtz:

“Simply put, the subjugation of Black people in America has always required a justification, namely that the failures of the Black community had nothing to do with the racism they endured. This mythology is central to understanding resistance to racial progress……Black success strips the fabric of the well-woven lie of Black inferiority and lays the threadbare”.

The same is true of the UK.

Black male narratives and mental health

The necessity of these racialised narratives of Black men to justify racism has remained constant despite some changes in legislation and policies. Even today, the concept of Black male criminality being linked to their genetics and culture is still there in society. However, in places such as Cleveland, UK which has one of the highest knife crime rates in Britain, the discussion was on addressing the deep poverty that these White men faced. In Glasgow, when this city had the highest knife crime rates, we started hearing of public health approaches that addressed the root causes. These conversations of root causes are relatively contemporary in policy spaces, but were all developed when there was a focus on White poverty and criminality. In contrast, historically, the conversation on criminality has looked at the Black male problem rather than the poverty and inequality problem that disproportionately impacts Black men, due to historical exclusions.

The same can be said of mental health, where Black men are treated much more harshly, and the discussion of root causes is too often put to the side. The focus has been on enforcement and heavy-handed approaches, while dismissing the historical context and root causes. Why? Because a narrative that Black men are just inherently more troubled and violent has been allowed to pervade and justify such treatment.

A recent study by Manchester Met confirmed that Black men have longer hospital stays, are more frequently re-admitted, are more likely to be deeply unhappy with their treatment, and are more frequently detained – taken into hospital against their will – through the criminal justice system than any other demographic. During detention, Black men are three times more likely to be subject to coercive practices such as excessive use of force and being physically restrained, including being pinned face down on the ground and forced to take medication. These experiences lead to long-term trauma for the men and their families.

As the study said:

‘The results were interpreted as ‘screaming silences’ regarding the history and impact of institutional discrimination and racism from police, mental health services, and academia historically known for doing research on and to Black communities, as opposed to for and with. This, and the dire consequences of these silences, has been known for over two decades but is rarely discussed’.

These narratives of Black men are dangerous and not only make people ‘feel bad’ but have real-world impacts on the everyday lives of Black men and their experience with mental health institutions.

Moving forward: Changing the narrative

On 1st November 2025, a Black man called Anthony Williams was charged with stabbing several people on a train in Huntingdon indiscriminately. First and foremost, the thoughts must be with the victims and their families of this dreadful, horrific crime. At the time of writing, we do not have all the details, but what we do know is that there was much discussion online about Black men being inherently criminals because of one man’s act. Yet when a White man drove into a crowd in Liverpool, injuring adults and children, it was seen as the act of an individual.

After the attack by Anthony Williams, I put on my Black Adidas hoodie and went for a run in the dark around 6 p.m. I felt more self-aware. It was not just me, but other Black men that I know felt the same way too. It was because they knew that the existing stereotypes about us were much more visible. I wonder if White men felt the same level of self-awareness about themselves following the attack in Liverpool?

I note this because there is a need to change the story of Black men, not only the policies and legislation. How we talk about Black men, portray them in society, all have real-world consequences on how they navigate their everyday lived worlds as well as their interactions with institutions (including those focused on mental health).

After Anthony Williams dreadful attack, the conversation quickly turned to how we can control, search and use surveillance on Black men more. However, the conversation on the wider sickness of our society as it pertains to Black men was kept off the agenda. There is no justification for the terrible attack on November 1st, but if we are to have a healthier and safer society, the societal and racialised drivers of poor mental health cannot be excluded from the conversation.

We must change the story, and we have an opportunity to do so through the everyday conversations, interactions with our colleagues, friends and with strangers. This too will make a difference. It will take more than a stroke of a pen for a change in law, but real change is implemented when it occurs in the hearts and minds of the people. This is difficult in a society that has platforms that push and normalise far-right racist narratives through their algorithms, but it is possible.

However, why engage in this anti-racist struggle and battle of the soul of Britain? Well, because racism does not only affect Black or Brown people, but it can also impact anyone. If our society is sick, then it will produce more sick people, which can negatively impact any of us.

For Men’s Mental Health Month (as Black men’s voices are too often unheard).

Matthew Johnson

CEO at Race on the Agenda